The Hidden Life of Books: Classification, Identity, and the Art of Browsing

What used bookstores tell us about knowledge and self-presentation

Last week I explored how the inhabitants’ of Gabriel García Márquez's fictional village of Macondo attempted to preserve their memory revealed an essential truth: classification systems, however well-intentioned, often fail to capture the complex web of meanings they seek to organise. This tension between categorisation and meaning plays out daily in spaces we rarely consider anthropologically: used bookshops, where knowledge is simultaneously preserved and fragmented through the very act of classification.'

The Dispersed Discipline

On a recent afternoon, as I wandered the stacks of local used bookshops in search of Anne Carson's poetry and accounts of Papua New Guinea's history, I encountered a peculiar phenomenon. The anthropology sections, where they existed, presented a curiously incomplete picture of the discipline - populated primarily by introductory texts, their spines displaying titles that promised broad surveys of human culture. Yet the works that most vibrantly embody the discipline were dispersed throughout the shops, sitting among history, political analysis, and regional studies.

This dispersal of anthropological thinking presents an intriguing paradox. While the discipline prides itself on studying the interconnectedness of human experience, its insights are missing from its own category, instead they are scattered across categorical boundaries that obscure their methodological origins. A book about Papua New Guinea's Trobriand Islanders might be filed under Oceanic History, while a study of their kula exchange system could be found in Economics. Marcel Mauss's seminal work on gift-giving practices might be shelved with sociology texts - fitting, perhaps, as Mauss himself, like many influential thinkers of his era including Émile Durkheim and later Pierre Bourdieu, identified as a sociologist rather than an anthropologist. Yet these disciplinary self-identifications only underscore how artificial such categorical boundaries can be, as Mauss's work on gift-giving has profoundly influenced anthropological thinking.

The Performance of Knowledge

The dialectic between knowledge and its performance was presented in an inadvertent ethnographic moment. While I was comparing editions of Anna Karenina (searching for the most reader-friendly font size because that novel is BIG and is text getting smaller?), I overheard a conversation between a grandmother and her teenage granddaughter that crystallised another dimension of how we relate to books as cultural objects.

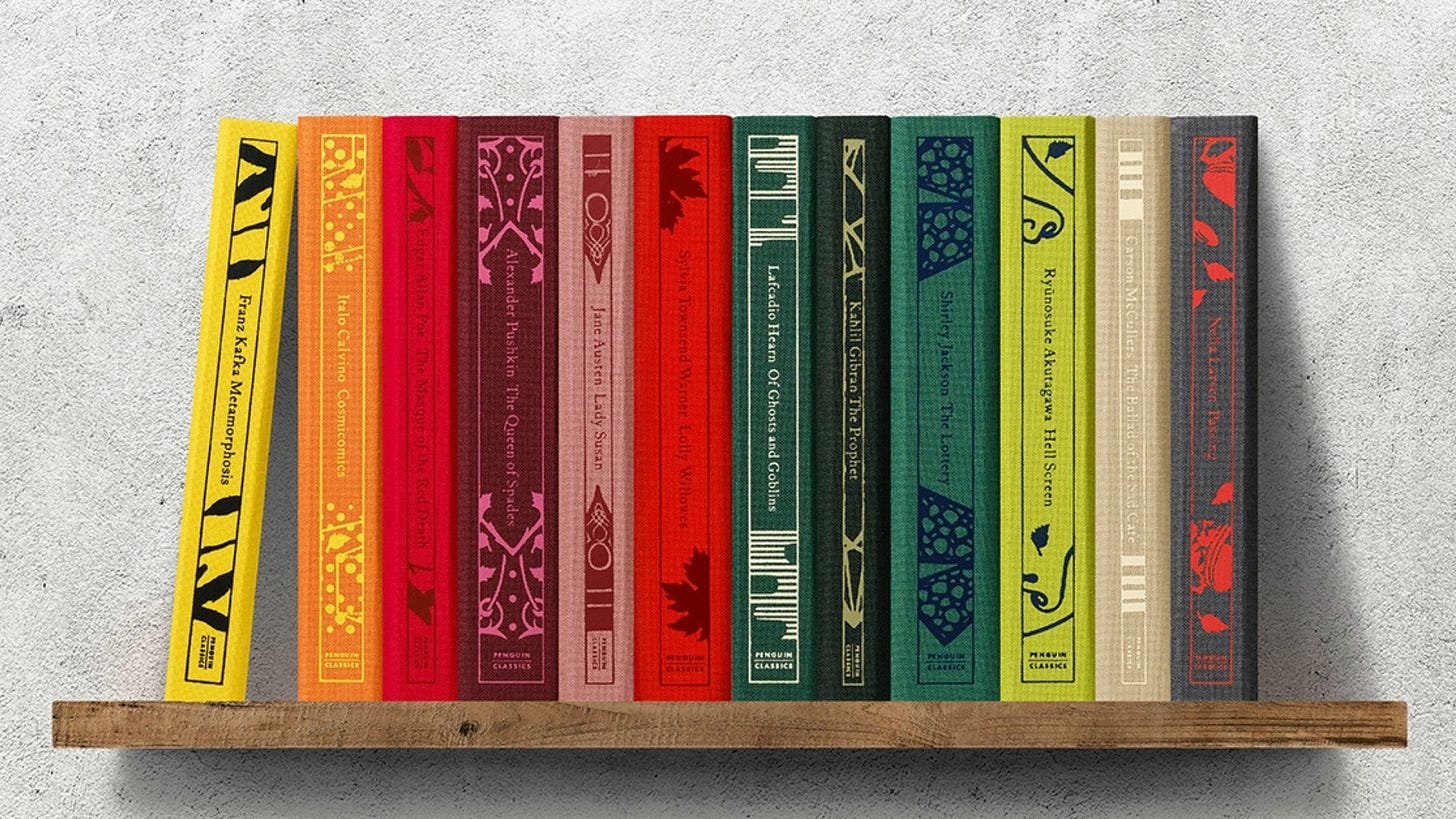

The scene unfolded around a display of clothbound classics - those beautifully designed editions that have become increasingly popular on social media. The granddaughter (dropping some birthday present related hints to her grandmother) demonstrated a fascinating linguistic dance: trying to articulate a desire for books while clearly prioritising their aesthetic value over their content. Her grandmother attempted to ascertain specific titles or authors, however in doing so encountered a kind of gentle resistance that revealed a generational shift in how books function as cultural artifacts. The granddaughter was noncommittal about authors and titles and even genres, rather, she was insistent that the books be pretty.

This interaction mirrors a broader transformation in our relationship with physical books. Just as Macondo's inhabitants found that labels could identify objects without preserving their meaning, these beautiful editions can signify literary culture without necessarily engaging with the texts themselves. The books themselves have ‘cultural capital’ - objects that communicate something about their owners regardless of whether their pages have ever been turned.

Classification and Identity

These parallel observations - the dispersed nature of anthropological knowledge and the performance of literary identity through aesthetic objects - speak to a larger question about how we organise and present knowledge in physical space. The used bookshop, with its carefully (if imperfectly) categorised shelves, attempts to impose order on the messy reality of human knowledge. Yet this very organisation reveals the arbitrary nature of our classification systems.

Consider how different the anthropology section appears to different viewers: To a first-year student, it might represent the foundational texts of a new discipline (at discount prices!). To a seasoned anthropologist, it might appear as a kind of phantom limb - present but incomplete, missing the vital connections that make the discipline whole. To the casual browser, it might suggest a field primarily concerned with theoretical abstractions rather than lived human experience, which couldn’t be further from the truth.

Similarly, the teenage girl's desire for beautiful editions of classic texts reveals how books function as both containers of knowledge and signals of identity. Her insistence to prioritise aesthetics over content suggests an awareness of how these objects are supposed to function (as texts to be read) versus how she intends to use them (as markers of cultural signification).

The Language of Spines

Long before Instagram-worthy clothbound editions, Penguin Books created their own visual language of knowledge through color-coded spines: green were generally for crime novels, cerise (or pink to some) was travel and adventure, dark blue was biographies, red for drama, purple for essays, and yellow was for miscellaneous titles that did not fit into any of the other categories. This colour-coding system became more than mere organisation. As Brian Morton noted in his reflection on Penguin's 80-year history these colors eventually became shorthand for intellectual identity, but not immediately. Initially, Morton writes, ‘it was feared that cheap books meant a net devaluation of writing itself’ and that ‘cheap books would mean fewer books sold’. But the opposite was true, Penguin paperback classics were embraced by the public and made literature affordable and accessible to the general public in much the same way Gutenberg's printing press democratised knowledge centuries earlier.

This historical precedent illuminates our contemporary relationship with books as both vessels of knowledge and markers of identity. Just as a row of colourful Penguin spines once signaled a literary mind, today's aesthetically curated bookshelves serve a similar function on social media. The difference lies not in the impulse to display knowledge - that has remained constant - but in how that display is mediated and consumed.

When Allen Lane founded Penguin, he aimed to make quality literature both affordable and attractive. The books needed to be, in Lane's words, “friendly” - accessible without sacrificing their cultural authority. Today's beautifully designed classics fulfill a similar dual function, though perhaps with the emphasis shifted more toward the aesthetic than Lane might have intended.

Beyond Categories

Perhaps what these observations reveal is the inherent limitation of any classification system - whether it's organising books in a shop or organising knowledge in our minds. Just as Macondo's inhabitants found that labels failed to preserve the living context of objects, our attempts to categorise knowledge often fail to capture its interconnected nature.

Yet there's something beautiful about how anthropological knowledge refuses to be confined to a single shelf. Its presence throughout the bookshop mirrors its presence throughout human experience - in our economic systems, our religious practices, our political structures, and our everyday interactions. The discipline's resistance to neat categorisation might be its greatest strength, reminding us that human knowledge, like human experience, defies simple classification.

Anthropology could truly be said to be an anti-discipline. For it will have no truck with the kind of intellectual colonialism that divides the world of knowledge into separate parcels for each discipline to rule.

Tim Ingold, 2018, Anthropology: Why It Matters

As for those beautiful clothbound classics? Perhaps they serve as a bridge between different ways of valuing books - as aesthetic objects and as vessels of knowledge. After all, many of us who now read voraciously began our relationship with books through some form of surface attraction, whether it was a beautiful cover, a film adaptation, or peer pressure. The challenge lies not in judging how others approach books, but in understanding what these approaches reveal about our changing relationship with knowledge and identity in an increasingly digital age.

References

Bourdieu, P., 2018. The forms of capital. In The sociology of economic life (pp. 78-92). Routledge.

Ingold T (2018) Anthropology: Why It Matters, Kindle Edition, Polity Press, Newark, United Kingdom.

Morton B (26 February 2015) ‘Spine tingling: 80 years of Penguin paperbacks’, BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3M67Kx1nm3wqSj7J7VwZRXv/spine-tingling-80-years-of-penguin-paperbacks.